Desdemona

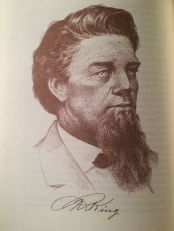

In the early days of Texas, almost everyone came from somewhere else. Richard King, for example, was born in New York City on 10 July 1824. His family was, as they say, dirt poor … and Irish. At the age of 9 years, Richard’s parents apprenticed him to a Manhattan jeweler. Apparently, Richard hated the work because in the next year he escaped indenture by stowing away aboard the cargo ship Desdemona, bound for Mobile, Alabama. When the crew discovered young Richard, they took him to Captain Hugh Monroe and First Officer Joe Holland, who after some deliberation, agreed to adopt the boy and teach him seamanship. Between 1835-41 (except for eight months of formal schooling with Holland’s family in Connecticut), Richard learned about steam boating on Alabama rivers. By the age of 16, Richard was a qualified steamboat pilot.

In 1842, Richard enlisted under Captain Henry Penny for service in the Seminole Wars in Florida. During his service there, he met Mifflin Kenedy, who became his life-long friend and business partner. Kenedy was a few years older than King, born on 8 June 1818 in Downingtown, Pennsylvania. Kenedy came from a Quaker family, educated in the common schools of Chester County. During the winter of 1834, Kenedy taught school, but in the spring, he signed on as a cabin boy aboard the Star of Philadelphia, which traded with Calcutta, India.

After serving at sea, Kenedy returned home where he taught school for a short time in 1836. Between 1836-42, he clerked aboard river boats plying the Ohio, Missouri, and Mississippi rivers. Between 1842-46, Kenedy sailed as a clerk and substitute captain on the Champion between Apalachicola and Chattahoochee rivers in Florida. This is when Kenedy first met Richard King. While Champion was undergoing repairs in Pittsburgh, Kenedy met Major John Saunders of the U. S. Army, an engineer who was securing boats for use by the Army on the Rio Grande during the Mexican American War. Major Saunders employed Kenedy as an assistant and later as master of the Corvette, where he served for the duration of the war. Richard King joined Kenedy on the Rio Grande, serving as master of the Colonel Cross. Together, King and Kenedy transported troops and supplies to US forces serving in South Texas and Northern Mexico.

After the war, Kenedy formed a partnership with Samuel A. Belden and James Walworth engaging in trade with Mexico. When the partnership dissolved, Kenedy shepherded a pack train of goods to Monterrey where he sold them for a good profit. King also remained on the border —as a steamboat captain. In 1850, King joined the steamboat firm of M. Kenedy & Company (1850-66). From 1866-74, the two men formed Kenedy & Company. For over two decades, King and Kenedy dominated the Rio Grande river trade. Both men were experienced seamen, and both men were risk takers.

The supremely confident King believed he could take a river boat almost anywhere. He was also an innovator, capable of designing specialized boats for narrow bends and fast currents on the Rio Grande. But what motivated King most was profit, which explains his dabbling in multiple undertakings with various associates. Of course, the money-maker in South Texas was land. Beginning in the 1850s, King speculated in Cameron County, Texas and buying lots in the emerging town of Brownsville. As his cash flow increased through successes on the river, he invested his profits in Nueces County land. After learning the hard way about fraudulent land schemes, he subsequently employed such men as Stephen Powers, James B. Wells, and Robert Kleberg[1] as attorneys in making land acquisitions.

The Running W Brand

Richard King first purchased land in the Nueces Strip in 1853, acquiring the 15,500-acre Rincón de Santa Gertrudis grant from the heirs of Juan Mendiola, which originated under an 1808 grant from the King of Spain. In the next year, King purchased the 53,000-acre Santa Gertrudis de la Garza Ranch. These two irregularly shaped properties became the nucleus of the now-famous King Ranch[2].

With partners Mifflin Kenedy and James Walworth, Richard King established an interest in cattle ranching. Initially, Kenedy was interested in raising sheep from Pennsylvania with an initial herd of 10,000 sheep which he installed near El Sal del Rey in Hidalgo County in 1854. In 1860, Kenedy bought into Santa Gertrudis ranch and became a full partner with King. When King and Kenedy dissolved their partnership in 1868, it took them 13-months to round up, count, and divide their stock in cattle, sheep, goats, and mules … animals spread from the Nueces River to the Rio Grande. With Kenedy’s share of the profits, he purchased the Laureles Ranch, twenty-two miles west of Corpus Christi, Texas[3].

In 1854, Richard King married Henrietta Maria Morse Chamberlin (1832-1925). Henrietta was born in Boonville, Missouri. Her mother Maria (Morse) passed away in 1835, and the absence of her father Hiram Chamberlin, due to his work as a Presbyterian Missionary, left her alone in her formative years. Her early years help to explain her strongly self-reliant and somewhat stoic personality. Henrietta attended the Female Institute of Holly Springs, Mississippi for two years beginning at the age of fourteen. In 1849, she joined her father in Brownsville, Texas. In 1854, she taught at the Rio Grande Female Institute. Henrietta accepted Richard King’s marriage proposal and the couple married on 10 December of that year. Richard and Henrietta raised five children, including Alice King Kleberg (namesake of Alice, Texas). One of Henrietta’s self-imposed tasks was the supervision of the housing and education needs of the families of Mexican ranch hands.

After Richard’s death in 1885, Henrietta assumed full ownership and control over the King Ranch, which by then included 500,000 acres of land between Corpus Christi and Brownsville —and around $500,000 of Richard’s debt.

In 1860, Texas cattle had little value beyond their hides and tallow. River trade was far more profitable. At the start of the American Civil War, Kenedy-King owned 26 boats. During the war, Kenedy-King were successful in shipping cotton along the Rio Grande to European buyers, horses and cattle, munitions, medical supplies, and clothing to Confederate field armies, and they were able to do this by registering their steamboat interests with the government of Mexico and moving their company offices to Matamoros. With every intention of disrupting south Texas trade, the Union Army captured Brownsville in 1863 and raided the King Ranch. When Colonel John S. (Rip) Ford retook South Texas in 1864, Kenedy and King resumed their business activities.

At the conclusion of the war, King went to Mexico where he remained until after President Andrew Johnson granted him a pardon in 1865. Afterwards, flush with profits from the war, King returned to Santa Gertrudis. In 1868, he and Kenedy dissolved their partnership and began operating as friendly competitors. The result of this was two of the most famous ranches in the American west. Each, in their own way, revolutionized the economy of Texas. Kenedy was the first to introduce fencing property, but both initiated overland cattle drives to northern markets, engaged in large-scale sheep, mule, and horse raising, and both approached cattle-breeding scientifically. Between 1869-84, King and Kenedy did more than anyone else to establish the American Ranching Industry. In these years, King alone sent more than 100,000 head of cattle to northern markets.

At the conclusion of the war, King went to Mexico where he remained until after President Andrew Johnson granted him a pardon in 1865. Afterwards, flush with profits from the war, King returned to Santa Gertrudis. In 1868, he and Kenedy dissolved their partnership and began operating as friendly competitors. The result of this was two of the most famous ranches in the American west. Each, in their own way, revolutionized the economy of Texas. Kenedy was the first to introduce fencing property, but both initiated overland cattle drives to northern markets, engaged in large-scale sheep, mule, and horse raising, and both approached cattle-breeding scientifically. Between 1869-84, King and Kenedy did more than anyone else to establish the American Ranching Industry. In these years, King alone sent more than 100,000 head of cattle to northern markets.

In the post-Civil War period, South Texas was in an economic transition period. For centuries, the economic foundation of the region of South Texas was the hacienda system[4]. Richard King saw no reason to change that, as in doing so, it would disrupt the culture of South Texas and Richard King realized that no one reacts well to change. King adopted the Hispanic legacy of the patron system, which provided social consistency, reliable labor, and at a reasonable cost.

Within the Spanish/Mexican system, a “patron” was the owner of the hacienda. He may or may not have lived on the hacienda but there was never any question that he was the lord and master of his vast holdings. In the sense that most estates were cash-poor, the arrangement was feudal in the sense that it incorporated a system of bartering of goods and services within the estate. As payment for their labor, hacienda residents received homes, schools, chapels, and they retained a percentage of goods grown or raised on the land. With these goods, they bartered for other goods and materials with people at other locations both on and off the hacienda.

On site management of the estate was a function of a paid administrator. On the King Ranch, management positions went to non-Hispanic lieutenants. It has always been the nature of peons to accept at face value their place in life, true under the Spanish and Mexican states, and equally accurate on South Texas ranches, as well.

King’s unfettered access to capital fueled his never-ending expansion of land and livestock and allowed him to displace competing ranchers and landowners. Both King and Kenedy despised the notion of the “open range,” and particularly loathed squatters whom he drove off his land at gunpoint. As a guarantee of available transportation, King invested heavily in railroads, notably the Corpus Christi-San Diego-Rio Grande narrow gauge railroads. He established packing houses, ice plants, and invested in harbor improvements at Corpus Christi. King’s fortune was the result of his anticipation of demands for beef, his implementation of volume production, and his effort to control transportation and markets.

All was not a bed of roses, however. The post-Civil War period in Texas was a dangerous time to be alive. Banditry existed on both sides of the Rio Grande. American outlaws routinely raided Mexican haciendas, murdering vaqueros and their families, stealing their horses and cattle. For men disenfranchised after the war, Mexican ranches were “easy pickings.” But white settlers in south Texas were targets for Mexican bandits, as well. In the minds of these bandits, white interlopers wrongfully seized previously Mexican owned lands in Texas and other border states. Men who perpetrated these crimes, from either side of the border, were of the worst sort. They were killers, rapists, and thieves. The King Ranch became a frequent target of such men, white or brown. Unlike many of the ranchers in South Texas, Richard King refused to put up with it.

Putting the King Ranch back together after the Civil War was no easy task. The Yankee Reconstruction Administration disbanded the Texas Rangers and all but ceded the Nueces Strip to Mexican bandits, who were happy to renew their raids on the hated gringos —and did so with brutal intensity. The next ten years were filled with two extremes: economic opportunity and danger. One of the great booms of American history was just beginning —the cattle drives. But Bandit raids from Mexico drove many of King’s neighbors out of business, and his whole empire was threatened. King forfeited tens of thousands of cattle during these so-called cattle wars. Among those living in South Texas, it seemed as if the Mexicans were about to seize back the land south of the Nueces that had been lost in the Mexican American War.

The prominent Mexican bandit was a man named Juan Nepomuceno Cortina Goseacochea (May 16, 1824 – October 30, 1894). Folks called him Cheno. He was an upper-class border character who had fought the Americans in the Mexican War and then lost his family’s land in and around Brownsville. Cortina had red hair and green eyes. He was charismatic and cruel. He was an opportunist who kept the border area in upheaval for two decades. No one hated gringos more than Cortina, and the focus of Cheno’s outrage was Richard King. Cortina often boasted that the gringo King was raising cattle for him and the Cortinista raids became King’s greatest outlaw challenge. The raids were frequent and so bad that King himself became a conspicuous target of the Cortinistas. Once, en route to meet with the American commission investigating cross border raids from Mexico, Cortinista thugs ambushed King and his party; a young German riding with King was killed in the resulting gun fight. In his desperation, King went so far as to join the Republican party in the vain hope that he could get help from the Reconstruction Administration, which for their part, seemed quite happy to see former Confederates suffer.

Finally, in 1875, at the end of Reconstruction, the Texas Rangers were reassembled. In one encounter a group of Rangers fought a pitched battle with a dozen cattle raiders who were driving a large herd of cattle belonging to the King Ranch. The Rangers killed every raider and dumped their bodies in the square at Brownsville as a sign that times had changed, and it set the tone for the bitter role the Rangers played during the so-called border wars … but it worked. Raids from Mexico slacked off, and when Porfirio Díaz seized power in Mexico in 1876 (with Richard King’s help) he made sure that such raids ended. King’s empire was saved.

Richard King was nothing if not a shrewd and ruthless businessman. To manage costs, King devised a scheme to make his trail bosses owners of the herds they drove to market. In addition to their salaries as employees of the King Ranch, trail bosses would sign a note for the cattle before driving them north, usually around February of each year. The drive would take roughly three months. Upon the sale of the herd to northern buyers, trail bosses would pay off their loans and still earn a profit greater than their ordinary wages. The system gave these men a stake in making sure that most of the cattle reached their destination at northern railheads.

Richard King was a hard-working man; his thirst for land insatiable, but by the early 1880’s his health deteriorated considerably. In 1885, feeling poorly, King traveled to San Antonio to see his doctor. He died at the Menger Hotel from stomach cancer on 14 April. At the time of his death, Richard King owned 614,000 acres (1,541 square miles).

The growth of the King Ranch created a demand for railroad service connecting the Rio Grande Valley to the rest of Texas, and of course, to serve the interests of the King Ranch. In the early 1900s, Henrietta King deeded a portion of the ranch to entice the construction of a town and bring the railroad to the edge of the King Ranch. In 1903, Robert J. Kleberg, Jr., who was then the manager of the King Ranch, formed the Kleberg Town and Improvement Company. The mission of the company was to plan and then build the town, eventually named Kingsville, three miles from the King Ranch headquarters. In that same year, the St. Louis-Brownsville-Mexico Railway reached Kingsville, the first train passing through on 4 July 1904. In 1913, Kingsville became the county seat of Kleberg County. The city’s first population boom occurred in 1920 with the discovery of oil and natural gas near Kingsville.

Henrietta Maria Morse Chamberlain King died on 31 March 1925, aged 92. At that time, the estimated worth of the King Ranch was $5.4 million. By this time, the King Ranch consisted of 997,445 acres of land (2,515 square miles), which did not include the estate’s Santa Gertrudis headquarters or the Kleberg’s Stillman and Lasater tracks. The estate was so expansive that it took another four years to pay the taxes, estimated at over $859,000. At the time of the stock market crash of 1929, the King Ranch was indebted to the sum of $3 million. In 1933, Bob Kleberg, Jr., leased a portion of land to the Humble Oil Company of Houston and this in effect put the King Ranch back on solid footing.

Sources:

- Lea, T. Captain King of Texas: The man who made the King ranch. Atlantic Monthly Press, 1957.

- Sanford, W. R., and Carl R. Green. Richard King: Texas Cattle Rancher. Enslow Press, 1997.

- The Handbook of Texas Online: Mifflin Kenedy.

Endnotes:

[1] Powers, Wells, and Kleberg played a key role in merging civil and common law in the establishment of land titles between the Nueces and Rio Grande rivers. Powers served in numerous influential positions in South Texas, including the chief justice of Cameron County, mayor of Brownsville, and the state Democratic party machine.

[2] By the time of King’s death in 1885, he owned land exceeding that of the state of Rhode Island. Today, the King Ranch encompasses 825,000-acres, covering 1,300 miles, situated on six South Texas counties: Brooks, Jim Wells, Kenedy, Kleberg, Nueces, and Willacy.

[3] This 131,000-acre ranch eventually passed into the hands of Henrietta King, Richard King’s widow, in 1906.

[4] The hacienda system was unique to Spanish colonies, although somewhat like the Roman latifundium. Some haciendas were plantations, mines, or factories, and some of them incorporated all these activities. In Mexico and South Texas, a hacienda was a landed estate of significant size; smaller holdings were estancias or rancheros.

If you add some subject tags to your posts, you will attract more readers. Hope this helps.

LikeLike

Richard King is an even more well-known name in Texas than is Bushy Bill. The King Ranch still dominates the southern part of Texas and has passed through several hands since it was first in those of Richard King. It’s been said that once one enters the main gate of the King Ranch, one still has a day’s ride to the main ranch house.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Imagine if Richard King had lived in the following 60 or 70 oil rich years.

https://aoghs.org/oil-almanac/king-ranch-oil/

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ford even named a truck after him.

LikeLike