There are 202,536 dentists in the United States today — roughly 61 dentists for every 100,000 citizens. Of those, only one stands out: John Henry Holliday. Historians tell us he was a gunslinger, a gambler, and a diseased sort. Was he diseased? Aye, he was that. And he was a gambler. But while he had the reputation of a gunslinger, some question whether it was true.

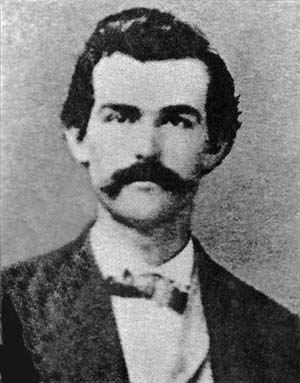

John Henry’s story is tragic but only one among many. One year after graduating from dental school, he was diagnosed with what was then described as consumption. He got it from his mother, Alice Jane McKey Holliday, who died in 1866. That was also tragic. Consumption is another way of saying tuberculosis. And, since no one with an ounce of brains wants anyone with tuberculosis breathing in their face during a dental exam, Holliday could not practice dentistry. This, too, was tragic because, in his short professional life, Holliday distinguished himself by offering suggestions about dental procedures and applications — published in professional journals and well received by his peers. (Picture of John Henry Holliday c.1877 shown right.)

What does a dentist who was denied the opportunity to practice his profession do for a living? In search of a more healthful environment, John Henry moved out west, where the arid climate was thought to facilitate recovery from the lung disease. Out west, there was only so much for a dentist to do besides gambling, which John Henry had learned to do at an early age. From all accounts, he was good at reading fellow gamblers’ faces and knowing when to fold ‘em.

“Doc” Holliday was a relatively small man. He was sick and frail, of slight stature, and trying to survive in an environment where robust men ran the roost. John Henry Holliday was no gunman. He was a poor shot. He was well-heeled, of course, but he was no master marksman. What he was — was a great pretender, but this was necessary to his survival. By making others think of him as a gunman, someone who carried three handguns and a stiletto knife, who (it was said) had killed 35 men, the false reputation guaranteed that other gunmen would leave him alone. Wyatt Earp knew this about Holliday. It was why he gave Holliday a shotgun just before the gunfight at O.K. Corral — even a blind man is deadly with a shotgun.

We also know that Doc Holliday was intensely loyal to his friends (the few who were worthy of the title) — and he never lacked courage. Pluck and audacity were something he shared in common with Wyatt Earp. During the fight at O.K. Corral, a fight that lasted for less than thirty seconds, thirty shots were exchanged. During the fight, Virgil and Morgan Earp were hit; several bullets passed through Holliday’s long coat — and yet neither Wyatt nor Doc Holliday flinched during the gunplay. Once Holliday had discharged his shotgun, he dropped it, pulled out his handguns, and continued the fight. He didn’t hit anyone, but neither did he shy away from danger.

Given Holliday’s relationship with the gunman, Johnny Ringo, a somewhat “in your face” exchange of threats and promises, some have suggested that John Henry had a death wish. We can’t say if he did, but it would be plausible and understandable if he did.

So, how many men do we know for sure that Doc Holliday killed in his long career as a gunfighter and a gambler? We know for sure he killed one man: Tom McLaury, who he shot at the O.K. Corral. If true, we must conclude that John Henry “Doc” Holliday was many things, but a gunfighter wasn’t one of them. He allegedly had a hand in the killing of Frank Stilwell and Florentino Cruz over in Tucson, but he was never charged with that crime, much less stand trial for it.

Huckleberry

The 1990s produced two of the most outstanding Westerns ever made. In their order of airing, they were Unforgiven (1992) and Tombstone (1993). None of the acting warranted an Academy Award (if that’s even important), but both stories told the story of plausible tragedies from the late 1800s. What makes Western films so popular is that the entire experience of settling the West was a series of tragedies — and the American people, whose descendants they are, respond to such stories.

In both films, the acting was top-notch and memorable. Whoever doesn’t enjoy a Clint Eastwood film shouldn’t be living in the United States anyway. And the truth is that Tombstone has become a cult classic. Val Kilmer starred in many films, but his performance as John “Doc” Holliday won us over for all time — and, in any case, as previously discussed, there may not have been a greater tragedy than the life of John Henry Holliday.

I appreciate the stories of the Old West — and have read as much as possible about the incident at Tombstone, Arizona. It was an interesting (and dangerous) time to be alive. Those of us who appreciate such stories are fascinated by the times. Did Johnny Ringo commit suicide, or was he murdered? The debate continues. I prefer to think Holliday gave Ringo his comeuppance (as portrayed in the film), but the evidence suggests otherwise. But let us not allow any facts to get in the way of a good myth. Ringo was a psychopath, so suicide is certainly plausible. Here’s another fact: Wyatt Earp was one gutsy fellow. What I wouldn’t give to sit down and talk to that gentleman over a cold beer.

My British wife didn’t quite understand some of the dialogue in Tombstone. She isn’t alone. But from everything we know of the post-Reconstruction period, such terms as “You’ll be a daisy if you do” and “I’ll be your huckleberry” were terms actually used back then — and we are told, spoken by Doc Holliday.

In his memoirs, actor Val Kilmer said that in the film, he spoke the words written for him by Kevin Jarre. I believe him. Jarre, however, may have missed the actual phrase spoken in 1880. Anyone who has been to Georgia (where Holliday was born and raised) appreciates the unique accents spoken there. Val Kilmer, who did an excellent rendition of the Georgia accent, spoke these words: “I’ll be your huckleberry.” The accent was perfect. But, while that’s what Jarre wrote, is that what the original phrase was?

In those days, a “huckle” was the handle affixed to a casket so that bearers could carry it to the grave site. Huckle bearer makes perfect sense from the context of the relationships between Holliday and Ringo. Now add the accent, and instead of “I’ll be your hucklebearer,” you come away with “I’ll be your huckleberry.” My British wife asked, “Okay, but what does this have to do with the phrase Huckleberry Friend in the song Moon River? Bless her … the question was appropriate, but context is important. She’d forgotten that in Mark Twain’s (Samuel Clemens’s) book, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, young Tom had a best friend named Huckleberry Finn. We’ve all had friends like young Finn … and remember them all our lives. Some of us (although only a few) become their hucklebearers many years later

👍love this

Sent from my iPhone

LikeLike

Thank you, sir …

LikeLike

See what you did, Mustang? You made me look it up…

Ringo ended up pushing UP the daisies…

LikeLike

Heh …

LikeLike

from Quora:

You ask about “You’re a daisy if you do.”

There’s some flush around the internet to the effect it’s a death threat. “You’ll be pushing up daisies [ if you do. ]” That’s a load of somewhat plausible twist. It falls flat. This particular quote is derived from something the real Doc Holliday is reported to have said. A gunfighter claimed “I’ve got you now, you son of a bitch,” to which Holliday rejoined, “Blaze away, you’re a daisy if you have.” This was widely reported, and not because people were like “WHAT?!”

The film updates the exchange to “I’ve got you now, you son of a bitch,” and “You’re a daisy if you do.” This is essentially same beans: same meaning. The first take is a touch grammatical: “You’re a daisy if you have [ me, as you claim to ].” The film’s “…if you do” has a more easy-to-follow catch-and-lilt to it, for modern ears. The meaning’s the same, though: nothing to do with a death threat. In the film, the opponent had already been mortally shot. Staggering out last threats, hoping to make good on ‘em.

He didn’t though. He wasn’t a daisy at all.

Calling someone “a daisy” in those days just meant they were a wonder, amazing. The best, a positive marvel. In short if you’re a daisy, you’re something special indeed. “A doozy” was a later mutation, and gained in other less-positive meanings as it went: such as an unexpected fall. “That first step’s a doozy!” But if you’re a daisy – you’re just splendid!

Was Doc Holliday calling the other guy splendid?

Nope.

He was saying he’d have to be, to pull off what he just claimed. Oh, you got me? You’d have to be splendid, buddy. Get me?

You’re a daisy if you do.

Nothing to do with “pushing up daisies”… oh, well. :(

LikeLike

I don’t know how we arrived at this long discussion about being a daisy. I, for one, never thought it had anything to do with “pushing up daisies.” But thank you for chiming in …

LikeLike

from this:

My British wife didn’t quite understand some of the dialogue in Tombstone. She isn’t alone. But from everything we know of the post-Reconstruction period, such terms as “You’ll be a daisy if you do” and “I’ll be your huckleberry” were terms actually used back then — and we are told, spoken by Doc Holliday.

LikeLike

Ah … okay, TS … thank you.

LikeLike

You elaborated as to “huckelberries” but were silent on the daisies.

I had to uncover “the rest of the story”. ;)

LikeLike

e-r-r-r-p. Huckle bearers. :(

LikeLike

Kilmer did an exceptional job with the Georgia dialect, and the explanation for Huckleberry is entirely plausible. Contrary to what many people may tell you, I was not alive in 1880 and can offer no first-hand information.

LikeLiked by 1 person