Background

It is possible to argue that the seeds of the American Civil War were planted before the ink was dry on the U.S. Constitution. Fourteen signers of the Declaration of Independence owned slaves. The founding fathers’ goal was to create a lasting union of states. To accomplish that, the founders had to accept the reality of slavery in the plantation south — otherwise, there would not have been the United States of America.

The Civil War began somewhat in earnest on 12 April 1861 when the South Carolina militia fired upon and forced the surrender of the Union garrison at Fort Sumter. By the early spring of 1864, the Union Army had made little progress in subduing the Confederacy in the eastern theater of operations. Its greatest success was in the western theater, particularly at Vicksburg, where nearly 30,000 rebel troops surrendered to Major General Ulysses Grant. Grant distinguished himself with victories at Fort Henry, Fort Donelson, Shiloh, and Chattanooga. A suitably impressed President Lincoln ordered Grant to Washington, promoted him to lieutenant general, and appointed him to command the Union Army.[1]

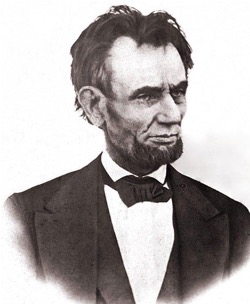

Lincoln and his generals

Abraham Lincoln never wanted a civil war and did everything he could to avoid it. He was wise enough to realize that whoever fired the first shot would likely lose the war if hostilities accompanied secession. He was right. It wasn’t until after South Carolina fired upon Fort Sumter that the northern states threw their full support behind Abraham Lincoln’s call for an army to preserve the Union.

Yet, despite all the Union’s advantages, the failed strategy and incompetence of the Union’s generals produced a protracted series of mediocre Union victories and jaw-dropping failures. Three years of failing to gain the upper hand produced a frustrated and psychologically depressed President Lincoln. As Lincoln searched for that one commander who could fight, Union Army leadership became a revolving door of senior officers (tried, failed, replaced). The longer the war went on, the more depressed Lincoln became.

The problem for Lincoln at the beginning of the war was that his generals were never his. With only a few exceptions, the Army’s generals were more politicians than warriors and most politically prominent before Lincoln assumed the presidency. And the generals knew that with only limited militia service himself years before, Mr. Lincoln was out of his depth in military matters. Mr. Lincoln’s generals were a cross to bear; the president soon found that he had no choice but to rely on men who, in many cases, viewed themselves more as the president’s equals than his subordinates. As a result, Union generals worked with Lincoln only when it suited them — and what suited many of them was to become president someday.

George B. McClellan, for example, frequently corresponded with his Democratic cronies. It was said that McClellan spent more time dabbling in politics than he did fighting the war. Joseph Hooker was known for his political intrigue, and William T. Sherman’s brother (and his in-laws) were prominent Republican politicians. George Meade was always available to speak to members of Congress, and he constantly flattered the president’s wife at White House functions, seeking her favor and support.

Of course, Lincoln’s generals were West Point graduates, but that did not make them exceptional generals — it only made them exceptional aristocrats. One prevailing opinion among historians is that whatever virtues possessed by Lincoln’s generals, militarily, they were disasters in gold-braided jackets. There were exceptions, of course — Ulysses S. Grant being one of them.

Grant’s Strategy

Lieutenant General Grant was critical of fighting the war in multiple locations with independent army commands. He wanted the Union army to fight together with only minor shifts in their objectives. Grant had no interest in conquering territory. He had but one focus: destroy the Confederate Army. To accomplish this, he intended to use all the forces available to him simultaneously, thus reducing rebel movements from one battlefield to another. His initial focus was the two largest Confederate armies: Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia and Johnson’s Army of Tennessee.

Grant’s plan for Meade’s Army of the Potomac was to move south to confront Lee between Richmond and Washington. He directed Butler’s Army of the James (River) toward Lee’s forces at Richmond and Petersburg. Sigel’s Army of the Shenandoah would move through the Shenandoah Valley, destroy the railroad line (denying Lee reinforcements), and destroy farms and granaries used to feed Confederate armies. Crook and Averell would attack the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad, the salt and lead mines, and then move eastward to join Sigel. Sherman would attack Georgia with similar goals.

Grant’s instructions to Meade were simple: pursue Lee wherever he goes. Still, Grant was under no illusions about a quick victory — he was fully prepared to fight a war of attrition. By 2 May 1864, Grant had four army corps positioned for his assault: (1) II Corps under Major General W. S. Hancock (four divisions of infantry); (2) V Corps under Major General G. K. Warren (four divisions of infantry); (3) VI Corps under Major General J. Sedgwick (3 divisions of infantry); IX Corps under Major General Burnside (four divisions of infantry, two regiments of cavalry, one regiment of artillery), and the Cavalry Corps under Major General Phil Sheridan (three divisions of cavalry) — around 100,000 combined troops.

Lee’s order of battle

General Lee commanded four army corps (three infantry with organic artillery and one cavalry) with three infantry divisions in each corps (except one corps had only two divisions). Lee’s corps commanders were Lieutenant General Longstreet (wounded) and Major General Richard H. Anderson (1st Corps); Lieutenant General Richard S. Ewell (2nd Corps); Lieutenant General Ambrose P. Hill (3rd Corps), and the Cavalry Corps under Major General J.E.B. Stuart, which included a horse artillery battalion. In total, Lee’s army consisted of around 62,000 men.

Battle of the Wilderness

On 4 May 1864, Meade’s force crossed the Rapidan River at three points, converging on the Wilderness Tavern near Spotsylvania. Thick vegetation and uneven terrain soon hindered Meade’s progress and limited his artillery’s fields of fire. There was limited visibility inside the dense forests, and Grant’s senior officers became worried that they were walking into a repeat of Chancellorsville. The size of the battle area was around 70 square miles in Spotsylvania and Orange counties.

Grant had no desire to re-fight an old battle, so he directed Meade to proceed to the open ground south and east of The Wilderness before initiating his assault against Lee. Logistics, however, is a war-stopper, and General Meade’s supply train involved around 4,300 wagons, 835 ambulances, and a large herd of cattle. To protect that logistics train, Meade had to either slow the pace of his advance or dedicate a protective force sufficient in size to keep enemy cavalry from destroying it. Nor was it easy to cross the Rapidan River with wagons and cattle. Circumstances required Meade to slow the pace of his advance.

Lee wanted to draw Grant into terrain favorable to him — the wilderness, where the hilly terrain and thick vegetation gave him a distinct advantage. On 4 May, General Lee had no idea what Grant intended, so to allow himself the flexibility to shift his forces where needed, Lee dispersed his army over an 18-mile front. Lee ordered Ewell and Hill to restrict Meade’s advance while Longstreet moved directly into Meade’s right flank from the southwest.

Meanwhile, General Meade was receiving false intelligence reports. Informed that his supply train was under attack from JEB Stuart’s cavalry, Meade directed Sheridan to investigate, which slowed his advance even more. There was no rebel threat to Meade’s army or his logistics train.

Grant established his headquarters alongside Meade’s. They arranged that Grant would concern himself with the strategy of the battle, and General Meade would focus on its tactical applications. Accordingly, Meade sent his army unopposed across the Rapidan on 4 May, but it was no easy task because supply wagons relied upon Meade’s ability to construct pontoon bridges. Additionally, in entering enemy territory without Sheridan’s cavalry, Meade’s advance was blind to enemy dispositions, particularly in the thick vegetation that impeded the Union’s forward-most elements. Grant remained confident that Sedgwick, Warren, and Hancock could hold back any Confederate assault until the logistics train moved closer to Meade’s main body.

Observing the Union Army’s crossing at the Rapidan River, Lee knew what Grant was likely to do. Lee believed it was imperative to draw Union forces into the Wilderness. To accomplish this, Lee ordered General Ewell east to Robertson’s Tavern and General Hill to New Verdiersville. The idea was to pin Grant down while Longstreet launched an attack against the Union flank from the southwest.

Battle Joined (5-7 May 1864)

The Battle of the Wilderness was General Grant’s first battle of the “Overland Campaign.” Grant’s plan involved a relentless and ruthless drive to destroy Lee’s army and capture Richmond, Virginia. This phase evolved into a bloody and inconclusive encounter, but the battle put the Confederates on the defensive and set the stage for Grant’s aggressive war of attrition and the Confederacy’s ultimate defeat.

As one might expect in a battle area as large as this one, the battle involved a series of engagements, each predicated on circumstances and events unique to a particular sector of the battlefront.

The Turnpike Fight

Warren’s V Corps advanced over farm lanes toward the Plank Road early on 5 May. Ewell’s 2nd Corps appeared to the west. Being advised of Ewell’s position, Grant ordered Meade, “If any opportunity presents itself of pitching into Lee’s army, do so without giving time for dispositions.” Accordingly, having assumed that Warren faced a small group of Confederates, Meade ordered an attack. Rather than commanding his force, Warren reacted to Meade’s orders without conducting a reconnaissance in force. Had he done so, he would have discovered that Ewell’s men had erected defensive positions west of Saunders Field, and this, in turn, would have prompted Warren to prep the battlespace with pre-assault artillery. He did not.

Warren’s front included Griffin’s division on the right and Wadsworth’s division on the left. The force was insufficient because Ewell’s defensive perimeter extended beyond Griffin’s right; any advance by Griffin’s brigades would subject his men to enfilade fire. Warren requested a delay until Sedgwick’s VI Corps could be brought up on Warren’s right, thus extending the line of advance. By early afternoon, an exasperated Meade ordered Warren to advance without delay. Meade’s blind insistence resulted in the bloody destruction of Bartlett’s Brigade.[2]

Cutler’s Iron Brigade[3]advanced through the thick wood and struck an Alabama brigade under Brigadier General Cullen Battle to the left of Bartlett’s Brigade. Cutler’s men initially pushed the rebels back, but their counter-attack forced Cutler’s men to withdraw.

Further to the left, near Higgerson’s farm, the Union brigades of Colonel Stone and Brigadier General Rice assaulted Dole’s Georgians and Daniel’s North Carolinians. Both efforts failed under heavy Confederate fire. General Warren lost his artillery to an overwhelming Confederate attack involving brutal hand-to-hand fighting. During this melee, the field caught fire, incinerating men from both sides, particularly among the wounded who could not escape.

When Sedgwick’s VI Corps reached the battlefield, Warren’s corps had quit the fight. Sedgwick nevertheless attacked the rebel line. After an hour-long series of assaults and counter-assaults, both sides disengaged to erect earthworks. At the end of the day, Lee lost two generals (Brigadier Generals Johnson and Stafford).

The Plank Road Fight

The Union men of Crawford’s Brigade were the first to detect the approach of General A. P. Hill’s 3rd Corps. Meade ordered Sedgewick to employ Getty’s Division to stop Hill’s advance at the intersection of Orange Plant Road and Brock Road. Getty’s use of Wilson’s cavalry succeeded in delaying Hill’s approach march, but the fighting evolved into mind-numbing hand-to-hand combat.

General Lee’s mobile command post was only a mile south of Hill’s position; Lee called for a war council, thinking the area was relatively secure. Union cavalry surprised Lee, Stuart, and Hill in the middle of these discussions. The Confederate generals ran in one direction, and the equally surprised Union troops ran in the opposite direction — missing an opportunity to end the war then and there.

As Hancock’s troops began arriving, Meade ordered Getty into the assault. Around 1600, Meade ordered Hancock’s II Corps northward to support Getty’s division. These troops were almost immediately pinned down by Confederate General Heth’s defensive line. Hancock sent his men forward into the line as soon as they arrived at the battle site, which forced Lee to commit Wilcox’s division, his reserve element, to reinforce Heth. Fierce fighting continued until nightfall, with neither side gaining an advantage.

The Second Day

General Grant based his plan for the following day on the assumption that Hill’s corps was exhausted. Accordingly, Hill became a primary target for Grant’s assault from the Orange Plank Road by II Corps and Getty’s division. Concurrently, Grant ordered V and VI Corps to resume their fight with Ewell on the Turnpike to prevent him from coming to Hill’s aid. Grant then directed Burnside to move his IX Corps through an area between the Turnpike and Plank Road and attack Hill’s rear echelon. If successful, Grant envisioned the destruction of Hill’s corps and a reconcentration against Ewell’s position.

Lee was aware of the situation along the Plank Road and realized Hill’s force was exhausted. He decided to replace Hill with Longstreet’s 1st Corps and ordered Longstreet to be in place before dawn on 6 May 1864. Once Longstreet arrived, Lee shifted Hill to the left to cover the open ground. General Longstreet received Lee’s order but estimated that he had time to rest his men, who on 5 May had spent most of the day on the march. Longstreet did not resume his march until after midnight. Night navigation is difficult — night movement is hazardous. Unsurprisingly, Longstreet’s Corps lost its way enroute on several occasions and failed to reach its designated position as ordered.

Hancock attacked General Hill at 0500. Wadsworth, Birney, and Mott (with Getty and Gibbon in support) successfully overwhelmed Hill’s Confederates. General Ewell’s men attacked the Union forces in the east at around 0445, but Sedgwick and Warren kept the Rebels pinned down. Despite excellent artillery support from Poague, the Yankees began pushing Ewell’s men back. Ewell’s corps was near to collapse when Brigadier General Gregg arrived with his 800-man Texas brigade. General Lee accompanied Gregg to a point so close to the forward edge of the battle area that the Texans refused to continue their attack until Lee withdrew to a place of relative safety.

Before Hancock could consolidate his new positions, Longstreet launched an attack with Major General Field on his left and Brigadier General Kershaw on his right. Union troops fell back a few hundred yards. Gregg’s Texans made a gallant charge, but Union forces badly chewed up the brigade. By 1000, only 250 Texans were left alive.

Unknown to Hancock, an unfinished railroad bed south of the Plank Road offered an excellent avenue for an attack by four rebel brigades. Leading the rebel charge, Brigadier General Mahone struck Hancock at around 1100. The suddenness of the attack stunned Hancock. At the same time, Longstreet resumed his primary attack, driving Hancock back to Brock Road. General Wadsworth fell mortally wounded.

Later in the day, General Longstreet accompanied Brigadier General Jenkins on a forward reconnaissance when the party encountered some of Mahone’s Virginians. These men mistook Longstreet for a Union officer and fired into his party, wounding Longstreet in the neck. Jenkins died instantly.[4] Longstreet relinquished his command to General Field. Soon after, the Confederate line fell into confusion; the resumption of the Rebel attack never materialized. Lee appointed Major General R. H. Anderson to temporary command of I Corps.

Fighting at the Orange Turnpike was inconclusive for most of the day. Brigadier General Gordon conducted a reconnaissance of the Union line at around 1000 and recommended that General Early authorize a flanking attack on Sedgwick’s right flank. Early dismissed the idea as too risky, and Ewell lacked sufficient men for an attack until around 1300 when R. D. Johnston’s brigade arrived. After the arrival of reinforcements, Early gave Gordon the go-ahead.

At 1800 hours, Gordon plunged his brigade into that of Union Brigadier General Alexander Shaler, forcing a union withdrawal. Gordon’s men captured Shaler and Brigadier General Truman Seymour — along with around 300 Union troops, and Sedgewick himself was almost taken, prisoner. The Union line fell back about a mile. Darkness and dense foliage halted Gordon’s effort, and Sedgwick stabilized his line and extended his right flank to the Germanna Plank Road.

Reports of Sedgewick’s collapse caused great excitement at Grant’s command post. Several of Grant’s staff officers moaned about not knowing what Lee might do next. A short-tempered Grant snapped at the moaners: “Start thinking about what we’re going to do and worry less about what Lee might do.”

George Custer’s brigade arrived at Brock Road at daylight on 6 May and filled the gap between Hancock and Gregg. Thomas Devin brought his brigade forward to join Custer, bringing artillery. Confederates under Brigadier General Thomas “Tex” Rosser assaulted Custer’s position at around 0800, but Devin’s battery turned the fight to favor Custer, forcing Rosser’s withdrawal.[5] Hancock, unsure of what Longstreet might do, kept two of his divisions behind the lines as possible reinforcements and/or surge troops.[6] As the fighting developed, Custer vs. Rosser, Gregg vs. Wickham, the Brock Road was blocked, denying Meade the opportunity of seizing the Spotsylvania Court House. At mid-afternoon, Gregg was withdrawn to Piney Branch Church, and Custer and Devin were redeployed to the metal works at Catharine’s Furnace.

The Third Day

On the morning of 7 May, General Grant reasoned that he had but two options available to him: he could either a frontal assault against strong Confederate defenses or maneuver his troops for a better effect. He maneuvered his force southward on Brock Road toward the Spotsylvania Court House. Grant reasoned that if he could place his army between Lee and Richmond, Lee would attack him across the ground more favorable to Grant. With that in mind, General Grant ordered preparations for a night march toward Spotsylvania (ten miles southeast). The distance wasn’t great but organizing 100,000 men to achieve it was no easy task.

Once Lee understood what Grant was up to, he quick-marched his Army to Spotsylvania, arriving ahead of Grant. By the time Grant’s Army approached the Court House, Lee’s men had already prepared their defense works. The Battle of the Spotsylvania Court House was a much more protracted fight, lasting through 21 May 1864.

The Casualties of the Wilderness

In terms of casualties, the Battle of the Wilderness ranks among the top five of the deadliest Civil War battles. The official Union after-action report listed 2,246 officers and men killed, 12,037 wounded, and 3,383 captured or “missing.” Union totals — 17,666. The actual number may have been higher. General Warren was later accused of deflating his Corps’ casualty figures. Grant gave up six brigadier generals in the fighting: two killed in action, two taken prisoner, and two wounded in action.

Confederate casualties included 1,477 killed, 7,866 wounded, and 1,690 captured or missing. Lee gave up three generals: Jones, Jenkins, and Stafford, killed, and Longstreet and Pegram were wounded/evacuated.

There was no “obvious” victor in the battle; neither side was driven from the field. Lee’s only field initiative was to beat Grant to Spotsylvania — otherwise, Lee’s rebels pursued a textbook defensive strategy. Grant never withdrew from the fight the way earlier Union generals had; he continued to press Lee and would not relent until Lee realized that the war was lost. As it turned out, General Longstreet’s advice to Lee was prescient: “Grant will fight you every day, and every hour of the day, until the end of the war.”

Sources:

- Carmichael, P. S. “Escaping the Shadow of Gettysburg: Richard Ewell and A.P. Hill at the Wilderness.” Chapel Hill, NC, 1997.

- Eicher, J. H. Civil War High Commands, Stanford University Press, 2001.

- Hogan, D. W. The Overland Campaign, 4 May – 15 June 1864. Center for Military History, 2014.

- Petty, A. The Battle of the Wilderness in Myth and Memory: Reconsidering Virginia’s Most Notorious Civil War Battlefield. Baton Rouge, Louisiana University Press, 2019.

Endnotes:

[1] Beginning in 1821, the title of the most senior Army officer was Commanding General, U.S. Army.

[2] Brigadier General William F. Bartlett received his second gunshot wound in this fight, a head wound, and he was evacuated for hospitalization. In a subsequent action at Petersburg, Bartlett lost the use of his prosthetic leg, and he was captured by Confederates and spent two months as a prisoner of war. Bartlett eventually passed away in 1876 from tuberculosis, aged 37 years.

[3] A devastatingly effective brigade that took so many casualties during the Battle of Gettysburg that Cutler’s force in 1864 was mostly comprised of raw recruits. Try as they might, the brigade’s experienced NCOs could not stop these youngsters from fleeing to the rear.

[4] This incident took place 4 miles from the place where Stonewall Jackson was also killed by his own men the previous year.

[5] Rosser was a courageous officer and a brilliant tactician. He was one of the few Confederate Officers to serve as a U.S. Volunteer flag rank officer after the Civil War.

[6] Hancock was unaware that Longstreet had been wounded and removed from the field. General Longstreet’s presence on the battlefield made every Union general nervous.

The constant marching, fighting, marching must have taken a miserable toll on the troops. And to what end? As you aptly explained, Mustang, there was no clear victory for either side.

The maneuvering of Union and Confederate troops seems to foreshadow the political maneuvering in the cold civil war of today by the Left and Right in this country. Although, human casualties are much smaller in number, the damage done to the country as a whole is reminiscent of the blow done to the nation a century and a half ago. Again, to what end? Like the Battle of the Wilderness, will there be no clear victor?

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’ve made an excellent point, Andy. “No clear victor” suggests so many things one doesn’t know where to begin. I suppose at the beginning when there was no majority arguing in favor of a pathway forward. The sentiments were broken down into thirds, but in order to make their case for independence, that one-third of the population had to convince their supporters that even though guilty of treason, they were real patriots. The real patriots were the loyalists. Another third didn’t care one way or the other — go along to get along. Some historians think we should stop using such terms as “patriots” and “loyalists” because no one is sure what those terms really mean … given the traitor/patriot paradigm. They suggest discussing this as a matter between Whigs (separatists) and Tories (loyalists) … which I suppose would mean that the one-third that didn’t care were back-benchers.

And the Civil War produced no majority, either. Not everyone living in the north supported emancipation, and not every dirt farmer living in the south supported slavery — and maybe the only people who understood what nullification meant were D.C. politicians.

In any case, I suspect that history will show us that regardless of the arguments between 1770 – 1776, or 1776 – 1789, it was all B.S. Thomas Jefferson argued in favor of nullification and of “spilling the blood from time to time to refresh the tree of liberty,” but I dare say that didn’t work out too well between 1861 – 1865, or 1865 – 1877.

Anyone who thinks they’re free, try not paying your tax bill and watch what happens.

LikeLike